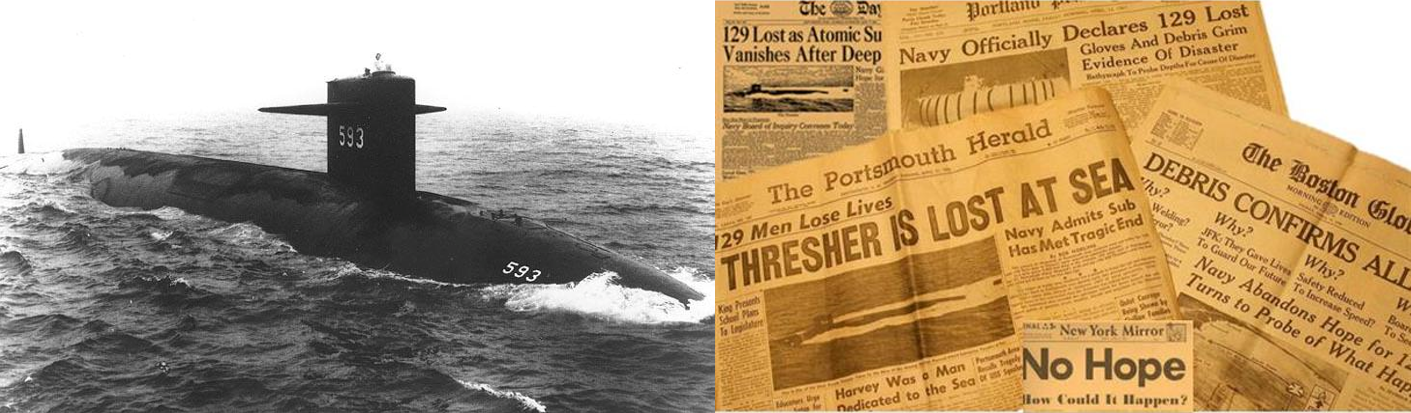

On her way out to the dive point, Thresher made several shallow dives in practice for her dive to test depth and performed them perfectly. Late that evening, Thresher completed the final leg of her journey to the dive point 220 miles off of Cape Cod in 8,400 feet of water. LT CDR John Wesley Harvey, Class of ’59 from Annapolis and veteran of three years and 100,000 miles on the USS Nautilus, prepared his crew to take Thresher to test depth.

The next morning, Thresher began her controlled dive in 100-foot increments. As she submerged, the increasing pressure of the ocean reminded the crew of its presence with familiar popping and creaking noises as the hull was compressed. Thresher sent routine messages to her escort ship, USS Skylark, as she progressed to depth. But at 9:17 a.m., Skylark received an unexpected garbled message, “…minor difficulties, have positive up-angle, attempting to blow.” And then…silence. USS Skylark repeatedly attempted to regain contact with Thresher, but there was no response. At approximately 9:18 a.m., USS Thresher was lost.

Despite the Navy’s rigorous investigation, the exact cause of this tragedy may never be known; however, the following is the likely sequence of events:

- One or more silver-braze piping joints in sea water systems failed, resulting in engine room flooding.

- Due to the ship’s design and system arrangements, the crew was unable to quickly access vital equipment to control the flooding.

- Saltwater spray on electrical components caused electrical panels to short circuit, the reactor plant to shut down and loss of propulsion power.

- The emergency main ballast tank blow system failed to operate properly. Restrictions in the piping system, coupled with excessive moisture in the compressed air, led to ice formation and subsequently blocked the path of air to the ballast tanks—Thresher could not return to the surface.

A court of inquiry was directed to gather all the facts and circumstances connected with the loss of the USS Thresher and death of personnel aboard, and to assign responsibility for the incident. The outcome was that the responsibility could not be placed on any one individual or organization, but that there were collective failures that most likely led to the loss of the USS Thresher. Examples included: inadequate quality assurance, inadequate training, deviation from building/design specifications, lack of communication, lack of proper approvals and schedule pressure.

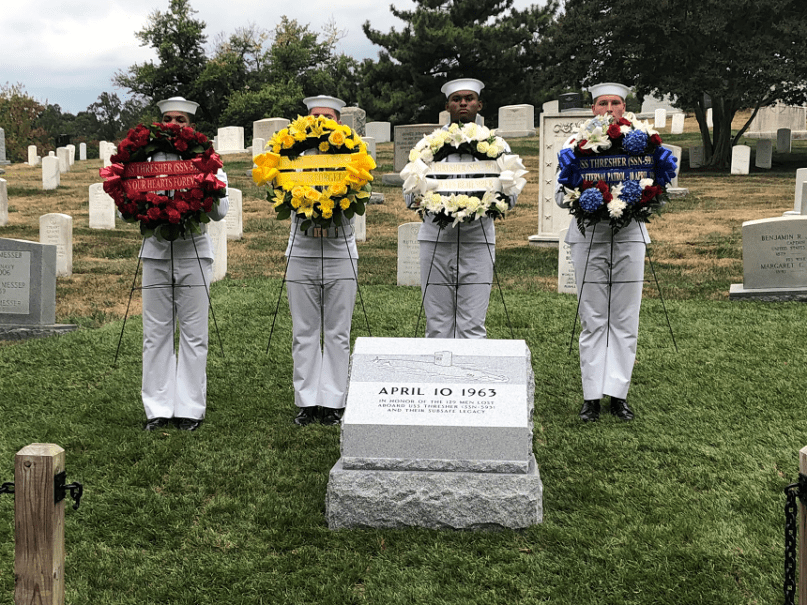

This Sunday, April 10, marks the 59th anniversary of the loss of Thresher—THE pinnacle event within the US Navy submarine community’s history.

This event represents both a tragedy and a major turning point to those involved in the design, construction and maintenance of United States Navy submarines. Following this tragedy, the US Navy resolved that future submarines would be designed and constructed in such a way that a similar catastrophe should never occur. As a result of this event, the Submarine Safety (SUBSAFE) program was developed in order to provide “maximum reasonable assurance of hull integrity to preclude flooding, and of the operability and integrity of critical systems and components to control and recover from a flooding casualty.” Maximum reasonable assurance is achieved by certifying that each submarine, based on objective quality evidence, meets all design, fabrication and testing requirements prior to certifying to the US Navy that the ship is ready for sea.

The same threats that doomed the Thresher exist today and must be mitigated with our diligence, which is why we must maintain the highest standards of design and engineering, challenge complacency in the workplace, provide clear and concise work package direction, assure our materials meet specification requirements and ensure that we do not compromise our ability to provide maximum reasonable assurance in any way. You may have read in the news last week about an explosion on USS Louisiana, SSBN 743, that occurred during a routine compartment air test. As a result, two people suffered serious injuries and were hospitalized for treatment. This was a timely reminder of how vulnerable we are to tragedy, even today, 59 years after the loss of the Thresher.

- Was the work paper flawed?

- Was there poor workmanship?

- Was work signed for that was not complete?

- Did complacency play in this event?

Imagine if this occurred in our shipyard and you worked on the equipment that failed. What would you be asking yourself today? “Was it my error that caused that event and those injuries?” Imagine the workers at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard when they learned of the loss of the Thresher. Imagine the questions that loomed in their heads for many, many years.

Complacency can only be addressed via discipline to standards and vigilance in execution. When you sign off a document, swipe your badge or electronically sign a record, you are participating in the ship certification process of eventually sending a ship to sea. Your signature is your contract with the ship, the crew and their families, that the work you did was done correctly and in accordance with procedural requirements. Your signature attests that the work you completed will positively contribute to the ship being able to operate as required and to submerge to test depth and return safely…every time.

What each of us does on a daily basis directly ensures the safety and wellbeing of the sailors that put their trust in us. They trust us to do our jobs right, every time. We should all take pride in our role in delivering the finest submarines in the world. No SUBSAFE-certified submarine has ever been lost. In fact three of them, the USS Hartford, USS San Fransisco and recently the USS Connecticut, all experienced significant at-sea collisions and sustained substantial damage, but because of the robustness of the design and the excellent workmanship you provide, they have and always will return home.

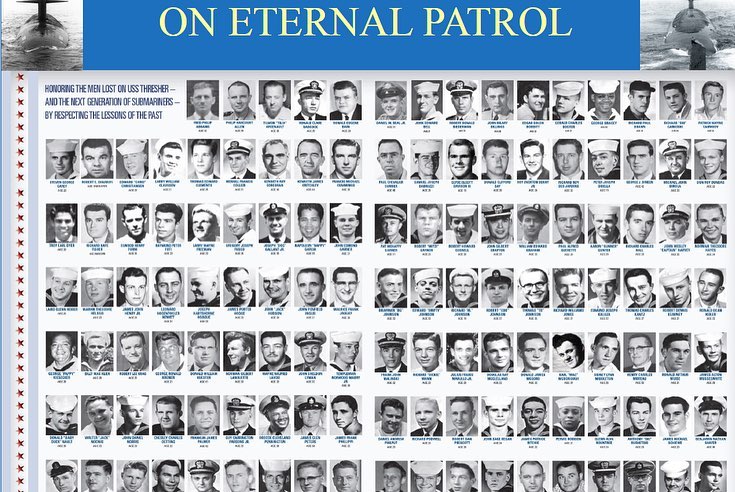

Thank you all for the excellence you provide to our product. Please keep the memory of the crew, the shipyard riders on the USS Thresher as well as their families, fresh in your mind each day and may the lessons learned from this tragedy shepherd you to achieve first-time quality in your work every day.

“They are remembered not as men who were, but as men who are; men, who because of their profession of the undersea, have given us greater knowledge of its mysteries, and opened broader paths for its exploration and use.” — E.W. Grenfell, Vice Admiral, United States Navy, Commander Submarine Force, United States Atlantic Fleet.

Stephen C. Kirkup

Director, Quality Assurance and Special Emphasis Programs